The history of the arabesque surface pattern

The origins of the arabesque surface pattern date back to Antiquity. Since then, it has spread from Europe to Japan via North Africa and the Middle East.

So many ornaments have been called "arabesques" over time that it is easy to get lost in this profusion of curves, volutes, counter-volutes and interlacings inspired by plants. In reality, this surface pattern is seen as a kind of "Ariadne's thread" that connects different eras, cultures and ornamental styles. Let's retrace the journey of this textile pattern inspired by world culture that inspires artists and decorators alike.

What is an arabesque textile pattern?

Definition

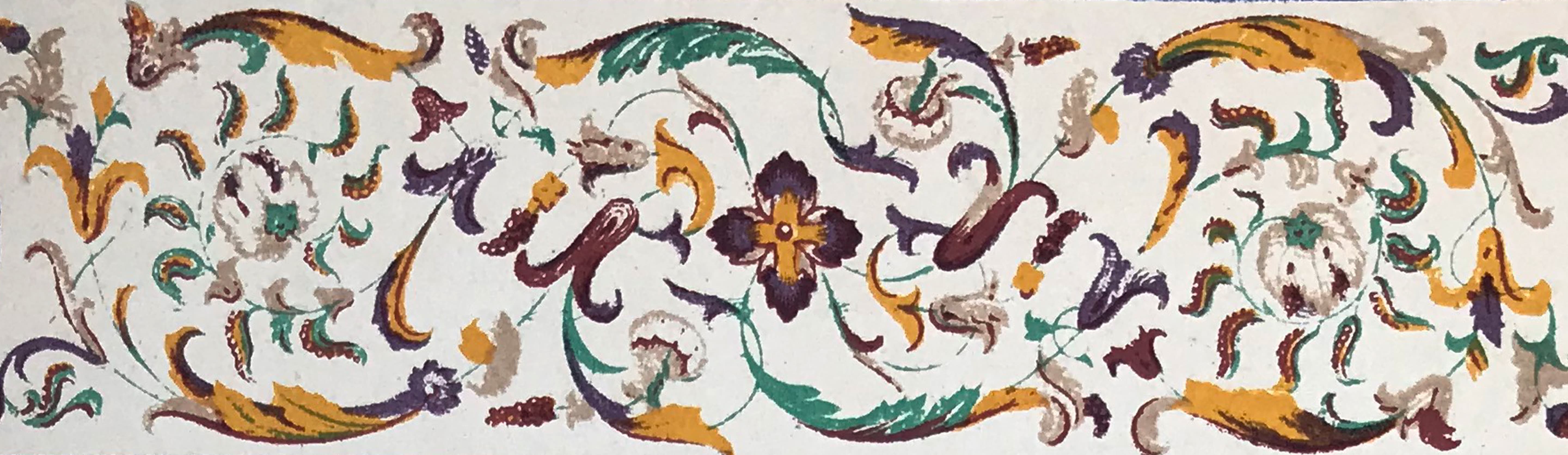

According to Robert, the arabesque surface pattern is an "ornament formed of interlaced letters, lines and foliage". From an aesthetic point of view, it is a set of intertwined undulating curves, inspired by stylized plant forms (leaves, stems, flowers, fruits). The composition of an arabesque textile pattern has the particularity of being symmetrical and/or repeated: it can be prolonged by repeating itself infinitely. Of naturalist inspiration, but not realistic, it generally respects a certain form of abstraction in relation to the natural appearance of plants to capture their essence.

Where does the name "arabesque" come from?

The term "arabesque" appeared during the Renaissance to name a style of decorative design omnipresent in Islamic art. Derived from the word "Arab", this term emphasizes the Arab-Muslim origin of these characteristic ornaments, composed of several intersecting sinuous lines and "foliage" (plant-inspired patterns, representing a stem curved in spirals decorated with foliage, flowers or stylized fruits). At the time, arabesque surface patterns were also called "moresques" or "Mauresques".

The Origins of the Arabesque surface pattern, from Antiquity to the Middle Ages

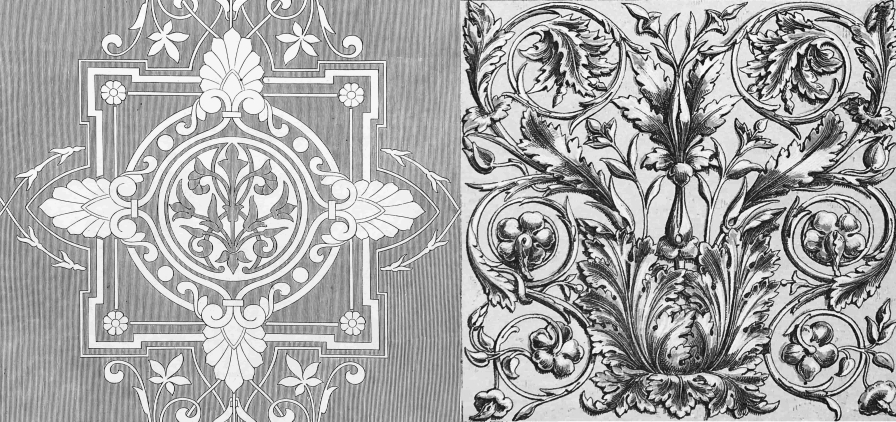

The roots of the arabesque date back to Antiquity, a period during which Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Greek and Roman civilizations regularly used patterns inspired by nature. Vegetal surface patterns are figurative, directly representing garlands and tangles of plants intended to adorn temples, palaces and objects of art. Many Greek remains still show today that acanthus scrolls or palms were very popular in architecture.

In ancient Rome, stylized plant surface patterns were associated with human and animal representations. These combinations would later inspire the Renaissance and grotesque art, as we will see later.

In the Middle Ages, with the rise of the Byzantine Empire and the spread of Islamic art, the stylized plant textile pattern began to detach itself from its figurative roots to become more abstract and repetitive. In Europe, this type of pattern is recurrent in the art of illumination, as evidenced by the illustration and decoration of medieval manuscripts. It even seems to have traveled to Asia, reinterpreted in Japan to become a traditional surface pattern called karakusa.

Between the 10th and 11th centuries, the naturalistic acanthus scroll evolved towards more refined forms, tending towards the essential. This transformation is particularly visible in Islamic art, which, for religious reasons, favors abstract forms. The arabesque, in its purely vegetal and geometric form, then finds its most accomplished expression.

A basic element of Islamic decorative art

The arabesque became a fundamental textile pattern of Islamic decorative art from the 8th century. The reluctance to represent human and animal figures led Muslim artists to turn to geometric and plant designs and to decorate places of worship, manuscripts, objects of everyday life. They are also an integral part of the architecture of many buildings.

The arabesque represents divine order and universal harmony. The stylized plant forms, winding and repeating endlessly, symbolize the eternal nature of creation and divine omnipresence. This pattern is often used to decorate ceramics inside and outside mosques, palaces, carved in the wood of sermon pulpits (minbar), integrated into tapestries ... Through the arabesque, artists seek to capture the beauty and perfection of the world created by God, without resorting to direct figuration.

In Islamic art, the arabesque surface pattern is never only vegetal, it is generally associated with geometric surface patterns (octagons, eight-pointed stars, etc.) and calligraphic textile patterns. The complex interlacing of arabesques combined with repetitive geometric shapes create visually rich compositions that draw the eye towards infinity, recalling the omnipresence of God. The calligraphic elements often take up verses from the Koran, thus reinforcing the spiritual message of the work. The combination of these three forms makes it possible to create symbolic and complex decorative compositions, where the vegetal pattern mixes with geometric shapes and Arabic letters to create a unified and harmonious work.

The Modern Arabesque Surface Pattern in Western Culture

Grotesque Art and Arabesque

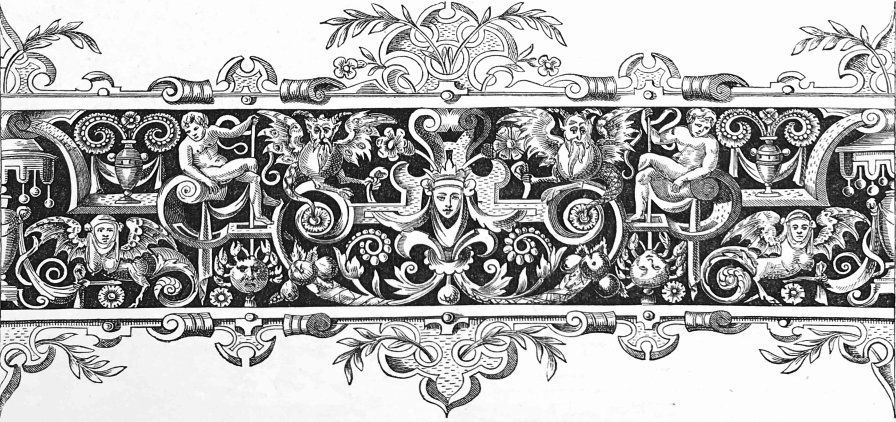

The link between the arabesque surface pattern and grotesque art requires context. Appearing during the Renaissance, grotesque art is so named because it is inspired by ancient remains unearthed at the end of the 15th century. These ancient buried Roman villas have the appearance of caves, and the frescoes they reveal are therefore called "grotesques". Mixing human, animal and plant forms in an elaborate ornamental style, these decorations immediately inspired the great painters of the Renaissance, including Raphael. At the end of the 16th century, the grotesque style moved away from the ancient references it sought to imitate. It tends towards graphic compositions based on the fanciful assembly of architectural elements, human and animal figures, hybrid chimerical creatures and decorative objects (flowers and leaves in bouquets, vases, garlands, etc.)

It is probably because of the omnipresence of repetitive interlacing of half-vegetal, half-animal forms that the grotesque style is regularly called "arabesque" between the 17th and 18th centuries. And this, despite its encyclopedic naturalism, which clearly differentiates it from the iconography of Islamic art.

This confusion of genres grouped under the same name still persists today: it makes "arabesque" an ambiguous term, and the "arabesque surface pattern" a graphic object offering great creative freedom!

Surprisingly, the arabesque is also linked to the famous blue patterns that made Moustiers earthenware famous. It was indeed under the influence of the Bérain style (an ornamentalist known for having renewed and lightened grotesque patterns) that their first arabesques were sketched.

In the 18th century, grotesques and the arabesque textile pattern strongly influenced European decorative art. Particularly in the Rococo and Baroque styles, characterized by exuberant, convoluted ornaments inspired by plant forms. These patterns took a resolutely figurative turn, but nevertheless retained the idea of intertwined and fluid lines, inherited from the Islamic arabesque.

William Morris' Acanthus Arabesque Surface Pattern

Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau, at the end of the 19th century, is the artistic movement that fully embraces the arabesque design in its modern version. This artistic movement, which draws inspiration largely from natural forms, seeks to reinvent ornamentation by moving away from strict symmetry to embrace curved and organic lines. The arabesque then becomes a symbol of artistic renewal and a tribute to nature, while retaining its oriental roots. Artists such as Gustav Klimt or Antoni Gaudi integrate these surface patterns into their works, creating swirling forms that mark this period indelibly.

The arabesque surface pattern did not wait for the West to give it its name to be enriched by contact with several civilizations. A true testimony to the richness of cultural exchanges throughout history, it has made it possible to create ornamental works that continue to fascinate with their complexity, harmony and universal symbolism.

Arabesque in Contemporary Arts

Today, the arabesque surface pattern remains an inexhaustible source of inspiration for creators and designers around the world. Whether in decorative design, painting or even embroidery, this Islamic surface pattern continues to establish itself as an essential element of decorative arts. Modern stencils make it possible to reproduce complex and repetitive arabesque patterns, making these forms accessible for contemporary interior decoration. These patterns are not limited to their historical dimension: they are reinvented in modern formats, exclusive collections, and premium products, whether textiles, tapestries, or art objects. Artists and craftsmen revisit floral arabesques, often in black and white, to create contemporary works inspired by tradition while meeting current tastes.

Luxury icons and major craft brands have also integrated the arabesque into their creations, notably with star textile patterns and repetitive geometric shapes. These find their way into high-quality objects, whether hand-made or printed using modern techniques such as digital engraving or screen printing. These patterns are particularly popular for specific applications, such as the design of decorative backgrounds, rugs, or mosaics.

In contemporary culture, the arabesque has transcended its origins to become a universal symbol of elegance and refinement. Whether in vintage geometric designs, floral ornaments, or even abstract painting surface patterns, this design continues to captivate with its fluid lines and ability to create visual harmony. Modern artists explore the intersection of traditional surface pattern and artistic innovation, often by blending traditional arabesques with typical elements of Art Deco or Art Nouveau. The arabesque is also invited to the creation of everyday products, such as album pages, or even decorative luxury products. In metered format, these surface patterns are found on textiles intended for furnishing or fashion.