Understand the symbols and specificities of Japanese textiles

The influence of Japanese textile patterns on fashion and decoration extends far beyond the Land of the Rising Sun. Deeply rooted in the Japanese art of living, Japanese textile patterns and traditional woven and embroidered fabrics reflect the richness of its history, beliefs and customs. Let's embark on a journey of discovery into a highly symbolic and traditional universe, at the origin of a multitude of patterns and colors that tell a thousand and one stories in harmony with Japanese culture.

The history of Japanese surface patterns

In Japanese, “pattern” is wagara. Initially inspired by chinese patterns, wagara have spanned the ages, adorning textiles, lacquerware, porcelain and decorative papers, evolving and enriching themselves over the course of history. Successive imperial dynasties, religion and mythology have influenced the development of an aesthetic and symbolism specific to the Land of the Rising Sun, through recurring themes still used in textile arts. Today, wagara represent a vast iconographic repertoire, imbued with strong beliefs and values. A true cultural treasure, sublimated by a particular vision of the obvious but fragile link that unites men and nature.

At the dawn of the first dynasties, Chinese and Korean influences

It was through contact with Korean weavers who came to settle in Japan that Japanese artisans learned linen and hemp weaving and sericulture. Located at the end of the Silk Road, the Japanese archipelago has benefited from multiple cultural, technical and artistic influences from China and Korea.

The numerous trade exchanges between China and Japan have allowed Japanese weavers to assimilate different Chinese textile traditions, in particular the methods of dyeing fabrics by ligature (kokechi), by wax reserve (rokechi), and by printing the fabric between two perforated boards (kyokechi). These decorative processes are used to decorate everyday clothing intended for the people. Embroidery also developed, decorating clothing intended for the aristocracy. Furthermore, the introduction of Buddhism in Japan in the 6th century allowed the spread of new imagery among a historically Shinto people. The first Japanese surface patterns therefore imitated Chinese patterns. The first wagaras were geometric, abstract, derived from natural or imaginary forms and based on the principles of Chinese cosmogony: fire, water, earth, wood and metal. Floral compositions were recurrent, representing real flowers (lotus, peony, honeysuckle, etc.) as well as arabesques, vine scrolls, etc. Throughout the Nara period (710-794), the surface patterns were available in primary or intermediate colors, in accordance with Chinese models.

The Heian period, the first golden age of Japanese patterns and textiles (794-1185)

During the Heian period, Japanese textile art distanced itself from Chinese culture. The imperial court gradually evolved towards new aesthetic standards. Dressing became a delicate art, thought out down to the smallest detail.

- Evolution of surface patterns

During this period, the design models from China evolved towards more graphic freedom. For example, we see the appearance of karakusa patterns, representations of stylized vines and spirals that replace Chinese arabesque and scroll patterns. Traditional Chinese flowers gave way to imaginary creations with several petals (kara-hana), increasingly large and complex, and the sakura pattern (cherry blossoms) gained popularity. Freed from certain Chinese aesthetic traditions, a clearly identifiable Japanese style gradually asserted itself.

- Yusoki: the repertoire of patterns used at the imperial court

The imperial court defined a repertoire of standardized textile patterns: the yusoki. It includes 27 models of designs traditionally used for weaving fabrics for clothing and furnishings, as well as the hundreds of combinations they can be used to create. This repertoire of surface patterns inspired by stylized geometric or natural shapes bears witness to the sensitivity of Japanese culture to naturalistic patterns. This source of inspiration has lasted to the present day.

- Junihitoe Costume

Another sign of Japan's "aesthetic emancipation": at court, the nishiki in supple and multi-colored silk of Chinese tradition was replaced in the 11th century by the osode, a stiff and voluminous ancestor of the kimono. It is at the origin of the junihitoe, a very refined women's costume with wide sleeves, which is worn in the form of several superimposed dresses (hitoe) of different colors, over a finer kosode in embroidered or unembroidered white silk. Depending on the historical period, this complex outfit can have up to 12 layers of dress and weigh around twenty kilos. The term kimono only appeared in the 13th century.

- Kasane no irome (or kasane-hiro), the art of combining colors

For their formal or ceremonial clothing, the Japanese aristocracy and high dignitaries turned to intermediate colors. Always closely linked to nature, these are associated with the 5 elements (fire, water, earth, wood and metal) but also with the seasons, the cardinal points, events, virtues, etc. The garment is then broken down into several superimposed dresses, a construction that allows colors to be combined in gradients thanks to different layers of more or less transparent fabrics. The color combinations are governed by an elaborate system called kasane-hiro. Choosing the right palette for your junihitoe becomes a complex and delicate art. Depending on the season or the occasion, women of the court might, for example, wear clothing in the color of "azalea coat" (shades of pink and orange) or "maple coat" (from crimson red to light ochre).

Warrior Spirit: The Impact of the Samurai on Textile Art (1192-1603)

In 1192, a new warrior class came to power. The time was one of civil wars, austerity, and sobriety. The moral values and rigor advocated by the samurai left little room for the refinement of the outfits worn during the Heian period. For men, armor was the order of the day.

- Surface patterns and color ranges under the sign of austerity

Having become inappropriate, sophisticated color hierarchy systems gave way to bright red, yellow, black, and white, widely used for armor and military accessories, but also to muted shades used for camouflage (the color “rotten leaf,” “jay feather blue,” etc.). Yusoki patterns were enriched with new, very simple geometric shapes that could be used as coats of arms (mon shô), but also with representations of objects from the warrior’s daily life: arrows, sword guards, horse harnesses, etc. The military elite nevertheless had some distractions, such as the tea ceremony (associated with very refined textiles for packaging and presenting goods) or Noh drama, whose sophisticated costumes required the work of skilled craftsmen.

- Development of free-style patterns

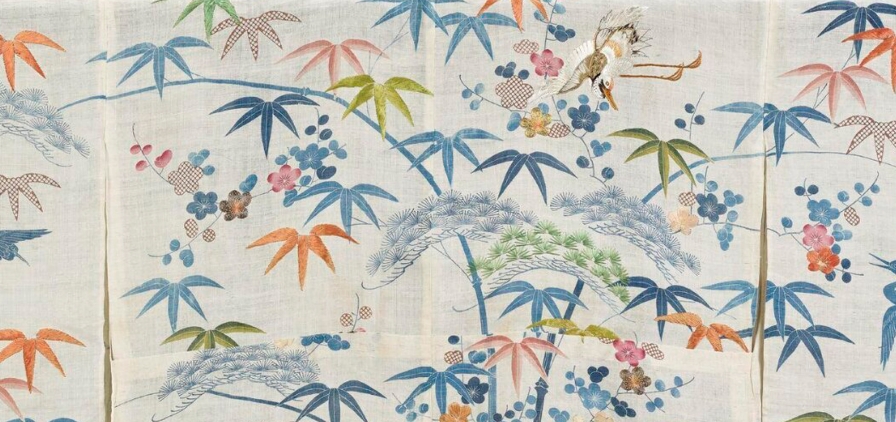

Women of all social classes wore the kosode (a small, fitted kimono with short sleeves). However, the social status of the wearer is easily identified by the type of fabric, the decorative techniques (dyeing, embroidery) and the types of designs used. As for the surface patterns, we observe a free style, exploiting different themes (plants, real or legendary animals, objects, etc.). The patterns are often grouped in seasonal combinations of good omen, or having a literary symbolism: pine, bamboo and plum tree, alone or together; or turtle and crane...

The diversification and democratization of textile art in the Edo period (1603-1868)

The Edo period was a turning point in the history of wagara. From the Momoyama period (1573-1600), the samurai era led to a certain political and economic stability, thanks to a unified Japan under a centralized feudal regime. Cultural exchanges with India and China resumed, promoting the restart and renewal of the Japanese textile industry. Kimonos decorated with patterns became accessible to all social classes: nobles, samurai, merchants and working classes.

- A rich and creative period

In this general atmosphere conducive to artistic expression, the Edo period bears witness to exemplary creativity in designing opulent geometric and floral surface patterns. Craftsmen used refined shibori, ink painting (kaki e), nui haku (embroidery with metallic foil)... In the middle of the Edo period, compositions became more complex, processes crossed, met and enriched each other. The kimono became a blank canvas on which the artists of the time did not hesitate to express themselves with realism through weaving, dyeing and embroidery. Narrative themes were inspired by nature but also by urban life, in an opulent display of techniques and motifs.

- Sumptuary laws

The craze for the kimono - decorated well beyond the codes respected for centuries by the upper class - was such that sumptuary laws were promulgated. The Edo period also saw the emergence of a new category of much more discreet patterns called komon (or edo komon) made up of a multitude of small dots printed using perforated stencils in mulberry leaf (kata zone technique). But these sumptuary laws, often diverted, led to a shift in refinement: if the designs became more sober "on the surface", the materials and processes were still just as luxurious. From then on, sophistication was expressed in a muted way, on the obi (kimono belt) and the under-kimono, richly colored and decorated.

The Meiji Period and Western Influence (1868-1912)

During the Meiji period, Japan opened up to the outside world, particularly the West. Industrialization and the adoption of Western production techniques made it possible to produce fabrics in greater quantities. While many materials and graphic styles borrowed from foreign textile art appeared, surface patterns experienced a certain standardization.

Although the Japanese now dress "in a Western style", traditional surface patterns have continued to live on in ceremonial clothing, decorative arts, interior textiles and everyday objects. They sometimes even merge with contemporary pop culture, but never forget their roots, anchored in Japanese history and customs.

The different Japanese surface patterns and their meanings

Even today, Japanese culture is imbued with multiple beliefs inherited from two great religions. In ancient times, Japan was only influenced by Shinto, a polytheistic and animistic religion that gave rise to many myths and beliefs, but it was deeply and lastingly marked by the introduction of Buddhism in the 6th century.

The wagara therefore exploit all sorts of themes and values inspired by Shinto or Buddhism, based on the worship of kami (forces of nature and ancestral spirits), the contemplation of the beauty of nature or seasonal cycles...

Geometric patterns

Concentric circles, triangles or hexagons: beneath their apparent simplicity, these refined wagara generally have a deep meaning. These geometric surface patterns can symbolize an element of nature, such as a flower, a religious belief, moral values... or all of these at once!

- Seigaiha: the waves

They are one of the most typical surface patterns of Japan and obviously pay homage to the sea, one of the pillars of Japanese culture. These stylized waves represented in the form of concentric arcs symbolize calm and tranquility. Seigaiha is often used as a sign of good fortune, peace and resilience.

- Yagazuri: arrows (or arrow feathers)

This textile motif of an object is originally reserved for men's clothing, the arrow motif has gradually become mixed. A lucky charm, bearer of values (determination, righteousness) Yagazuri is also associated with several symbols, including that of a happy marriage. On the occasion of a union, this motif materializes a wish: that the bride, like an arrow shot from a bow, does not return to her parents' home

- Asanoha: hemp leaves

Highly stylized, Asanoha represents hemp leaves arranged in a star shape. This fast-growing, resistant plant is a symbol of strength and protection. Often used for clothing and children's textile patterns, Asanoha carries with it the hope of seeing them grow up serenely and in good health. This simple and graphic surface pattern is also used to decorate upholstery textiles, canvas curtains and tablecloths..

- Kikko: the turtle shell

This hexagonal pattern is inspired by the “scales” of turtle shells. In Japanese culture, this animal symbolizes protection and longevity. We find this pattern on formal clothing, samurai armor and in traditional architecture (tiles, ceilings, etc.)

- Igeta: the sharp (or grid)

Of course, the resemblance is not immediately obvious, but the igeta motif does indeed represent a well. Likened to a water source, this very popular Japanese wagara is a symbol of life and abundance.

- Karakusa: the arabesques

This classic surface pattern was imported from China during the Nara period. Often green in color, it represents plants in full growth and brings good luck.

- Shippô: superimposed circles

Used since the Nara period (8th century), the Shippô motif is inspired by cloisonné enamel creations. It symbolizes the 7 treasures of Buddhism and has long been used on women's clothing.

- Komon or same komon: shark skin

From a distance, this very discreet pattern could almost pass for a surface pattern with a plain background. Up close, the concentric dotted circles that compose it evoke shark skin. This high-quality, subtle effect is obtained by dyeing, applied using a microperforated stencil.

- Uroko: triangular scales

This pattern composed of two-tone triangles symbolically represents fish, snake or dragon scales. It protects and brings good luck, which undoubtedly explains why uroko was so popular for making the lining of kimonos, or for adorning the obi of Japanese warriors. It is the traditional talisman par excellence of Japanese culture.

The repetitive and symmetrical structure of many geometric wagara textile patterns finds a natural parallel in Art Deco seamless pattern, which are also based on orderly shapes and regular lines.

Floral Surface Patterns (Kacho)

Omnipresent in Japanese textiles, floral textile patterns each have their own meaning. And since Japanese traditions attach extreme importance to the cycles of nature and seasonality, many of them are only used during the time of year that corresponds to their blooming.

- Sakura: the cherry blossom

Typically Japanese, cherry blossoms are one of the emblems of the Land of the Rising Sun. These slender and ephemeral flowers remind us that life is transitory, just like beauty. Sakura returns each year in spring, when the Japanese cherry trees bloom. A symbol of joy and renewal, this classic wagara is often worn during spring ceremonies and festivals.

- Botan: the peony

In Japan, the peony is considered the queen of flowers and a symbol of femininity. It is associated with wealth and strong values such as honor and courage. Botan is a motif that is very regularly used to adorn luxurious clothing and accessories (silk kimono, embroidered obi, etc.) for weddings and other important events. It is traditionally thought to bring luck and prosperity.

- Kiku: the chrysanthemum

This flower also occupies a special place in Japanese culture, and for good reason: it is the symbol of the imperial family. Embodying longevity and renewal, the chrysanthemum is generally displayed in autumn, on formal kimonos and decorative textiles (curtains, cushions, etc.)

- Tsubaki: the camellia

The camellia blooms at the very end of winter. Since the Edo period, Japanese customs and traditions have made it the flower of hope, love and desire, but it can have other meanings depending on its color (bad luck, waiting, etc.)

- Ume: the plum tree

Just like the sakura, the ume motif rhymes with beauty and elegance. But it is also attributed protective virtues from Japanese folklore, since the plum tree is said to chase away malicious oni, a type of yokai (evil spirits).

- Shoubu: the Japanese iris

Very easily identifiable by its long, tapered leaves and 3 graceful petals, the Japanese iris can symbolize wisdom, hope or faith.

- Asagao: the morning glory

Used as a motif since the Heian period, the morning glory opens in the morning and closes as soon as night falls. It is frequently used to adorn the kimonos of geishas.

Patterns inspired by nature and the elements

In this category of wagara, we find representations of landscapes, animals and various natural elements that are very important in Japanese aesthetics. They take a contemplative look at the possible harmony between man and nature.

- Yama: the mountain

In Japanese culture, the mountain is considered a sacred place, which necessarily commands respect. A symbol of strength and stability, close to the divinities, yama is a respectful homage to nature in all its majesty.

- Kawa: the river

This surface pattern symbolizing rivers and waterways captures nature in motion, the flow of life and its impermanence. Kawa is often combined with floral patterns to create idealized scenes and sublime landscapes. Its popularity increases in summer, printed or embroidered on kimonos worn during festivals.

- Take: bamboo

In Japan, this common but elegant plant that grows and multiplies quickly rhymes with prosperity, flexibility and robustness. Represented in the form of leaves, it is a symbol of inner peace and tranquility.

- Kiri: the Pawlonia

This tree native to China and Korea has its importance in Japan: custom dictates that a pawlonia shrub is planted when a little girl is born, and cut down when she gets married. The kiri motif is represented in the form of 3 leaves. According to Japanese traditions, kiri is often combined with bamboo (take) as a sign of good fortune.

- Matsu: the pine

The pine is the subject of many beliefs related to Shintoism. This resistant tree is said to be used by the kami to descend to earth. It is also said to have the ability to repel demons and evil spirits... It is therefore attributed protective virtues and the matsu is used as a symbol of longevity on textiles. The Shinto Matsuba is a wagara representing a very simple sowing of pine needles, a sign of longevity and perseverance.

- Momiji: the maple leaf

Admired in autumn for the changing colours of its leaves, the maple has inspired Japan since ancient times. Momiji embodies change and transition by highlighting the ephemeral aspect of life. This vegetal motif is ideal for a textile brand’s autumn collection.

- Kumo (Unki in feudal Japan): the cloud

Mist (tatewaku) and clouds (kumo) were wagara frequently used together on the stoles (kesa) and robes of Buddhist priests. They metaphorically represent a certain capacity for detachment and spiritual elevation.

Animal Motifs

Real or mythical, animals have long been a valuable source of inspiration for Japanese textiles. Generally associated with good omens and noble values, animal surface patterns are everywhere!

- Tsuru: the crane

Inseparable from Japanese traditions, this graceful bird is a symbol of luck and longevity. Initially reserved for people of high lineage, tsuru is one of the most popular and most exploited motifs, whether in origami, decorative paper or textiles.

- Kujaku: the peacock

The majestic appearance of the peacock has made it a very popular graphic theme in Japan. This “good in every way” motif carries values of love, goodwill, education and attention.

- Tora: the tiger

This major figure of Buddhism is a symbol of power, but also of elegance and subtlety. This species is not represented in Japan, which does not prevent this superb animal from being part of the textile patterns that can be found in Japan.

- Koi: the carp

The koi carp is a promise of luck, happiness and prosperity. This fish carries noble values such as courage and perseverance. Enough good reasons for it to figure prominently among the animal surface patterns commonly used in Japan.

- Usagi: the rabbit

Sometimes represented alone, sometimes accompanied by the moon (notably on the occasion of Tsukimi, the traditional full moon festival), the rabbit is a mythical animal in the eyes of the Japanese who attribute to it great intelligence, great generosity and a sense of devotion.

- Kame: the turtle

The longevity of turtles is well known. Sometimes represented with a shell covered in algae (as happens with old sea turtles), this animal is an omen of long life, in addition to bringing good luck.

- Tombo: the dragonfly

Moving forward in all circumstances is the best way to achieve your goal. This is the message carried by the slender dragonfly, a motif that symbolizes courage and determination.

- Cho: the butterfly

The butterfly is one of the most appropriate symbols to embody evolution, transformation, even immortality or reincarnation. This is how the Japanese see it, who never fail to depict sublime butterflies on their textiles. As a couple, it predicts a fulfilling marriage.

- Chidori: the plover

Despite its modest size, this small migratory bird, always ready to brave storms, embodies courage, determination, willpower, but also family security and the unbreakable bonds of love or friendship.

- Fukuro: the owl or the owl

Until the Meiji period, which saw the development of Western influence in Japan, the owl and the owl were signs of luck and protection. Nowadays, as in many other places in the world, these surfacepatterns printed on textile or paper rather symbolize knowledge and wisdom.

- Houou: the phoenix

When it appears, the phoenix brings prosperity, peace and harmony. Alone or associated with the Kirin (described a little later) this fabulous animal is therefore a very good omen!

- Ryuu (or Tatsu): the dragon

Beyond its power and impressive appearance, Japanese culture sees the dragon as a benevolent creature bringing luck and good fortune.

- Tanuki: the raccoon dog (Asian raccoon)

The Tanuki, a type of raccoon, is a well-known animal in Asia, and a typical creature of Japanese folklore because it has the ability to take on any appearance. This animal is enjoying growing success in the form of textile patterns. "Pompoko", an animated film by the famous Hayao Miyasaki that gives the Tanuki the lead role, is probably not for nothing...

- Kirin or Qilin: a mythical creature

Stronger than the platypus, the Kirin resembles both a horse and a deer, while having scales, fur and horns. This strange creature that looks a bit like a dragon is part of the myths and legends of Japan, but it is always a sign of harmony and a very good omen.

Some traditional or cosmogonic motifs

- Mon or kamon: family crests

Appearing in the middle of the Heian period, mon were originally a well-defined category of motifs, coats of arms used as a crest by samurai clans to easily identify themselves in combat. This custom then spread to all the nobility and nowadays, all Japanese citizens can own one. The hanabishi motif (water chestnut flowers) which probably inspired the Mitsubishi group logo, is an example.

There are more than 20,000 different heraldic emblems, divided into 5 categories: plants, animals, natural elements, buildings and vehicles, tools and abstract signs.

- Fujin and Raijin (or Raiden): the spirits (Kami) of wind and thunder

These deities are twin brothers from Japanese mythology. One is the god of wind (Fujin), the other that of lightning and thunder (Raijin). Both feared and venerated, these kami rarely go one without the other and sometimes appear in the form of patterns on textiles.

- Shichi Fukujin: the seven divinities of happiness

From Buddhism, the 7 divinities of Happiness are very auspicious, since they symbolize luck and good fortune. Each embodies a virtue or a blessing: integrity, prosperity, generosity, dignity, popularity, longevity and magnanimity. They can be represented together, sometimes on their ship (Takarabune), or separately.

Meaning of the Most Well-Known Japanese Patterns

|

Japanese Pattern |

Category |

Meaning |

|---|---|---|

|

Seigaiha (waves) |

Geometric |

Calm, tranquility, good fortune, peace, resilience |

|

Asanoha (hemp leaves) |

Geometric |

Strength, protection, growth |

|

Kikkō (tortoise shell) |

Geometric |

Protection, longevity |

|

Shippō (overlapping circles) |

Geometric |

The Seven Treasures of Buddhism |

|

Uroko (triangular scales) |

Geometric |

Protection, traditional talisman |

|

Sakura (cherry blossom) |

Floral |

Joy, renewal |

|

Botan (peony) |

Floral |

Femininity, wealth, honor, courage, prosperity |

|

Kiku (chrysanthemum) |

Floral |

Longevity, renewal, imperial symbol |

|

Tsuru (crane) |

Animal |

Good luck, longevity, nobility |

|

Koi (carp) |

Animal |

Luck, happiness, prosperity, courage, perseverance |

The specificities of Japanese fabric

Japanese textiles are the result of very old craft traditions and know-how that have become more sophisticated over time. In addition to the patterns, Japanese fabrics are distinguished by certain manufacturing techniques and the high quality of the materials used. Japanese textile art is distinguished by the attention paid to detail, the harmony of colors and textures, as well as the durability of the finished products.

Manufacturing techniques

Japanese fabric manufacturing techniques are varied and complex, often passed down from generation to generation. Among the best known are:

- Shibori: This tie-dyeing technique creates irregular and unique surface patterns on the fabric. Each piece of shibori is different, because the knotting and dyeing process can never be reproduced exactly the same way.

- Kasuri: This is what ikat is called in Japan. This weaving technique requires dyeing the threads before weaving them in order to create blurred or irregular patterns on the fabric. Kasuri is often used for kimonos and other traditional clothing.

- Yuzen: This hand-dyeing technique created in the Edo period combines brushwork, batik, and the application of precious materials. It creates extremely detailed and colorful surface patterns on the fabric. Yuzen is particularly popular for ceremonial kimonos because of its visual appeal.

- Chirimen: This silk with a wavy texture is used to make kimonos that drape elegantly.

Materials Used

Traditional Japanese fabrics are often made from high-quality natural materials, such as silk, cotton, and linen. The choice of material depends on the intended use of the fabric, as well as the season.

- Silk: Silk has long been the preferred material for traditional kimonos, obis, and other textile accessories worn during ceremonies. It is prized for its softness, luster, and ability to drape elegantly over the body.

- Cotton: Japanese cotton is renowned for its softness and durability. Originating from Nishiwaki (Hyogo region), banshu-ori is the pride of Japan. This cotton woven and dyed in the Hyogo region has been appreciated for more than two centuries.

- Linen: Linen is used mainly for summer clothing for its lightness and ability to absorb moisture. Linen textiles are often decorated with floral or geometric patterns, perfect for summer kimonos and indoor clothing.

Contemporary use of Japanese fabrics

Today, Japanese fabrics are used not only for traditional clothing such as kimonos, but also for much more modern applications. Seduced by their quality and unique surface patterns, fashion designers around the world integrate Japanese fabrics into their collections.

They are also popular in the field of interior decoration. Cushions, curtains and tablecloths made from Japanese fabrics are very popular in interiors for their elegant style and authenticity.

Like the tenugi (a thin traditional cotton towel measuring approximately 35 cm x 90 cm), many typical Japanese fabrics have become versatile accessories, used on all sorts of occasions as tea towels, aprons, head coverings, handkerchiefs, gift wrapping, or wall decorations. And while the fukusa, a small, very formal rectangle of fabric, is still mainly used for tea ceremonies and wrapping precious gifts in Japan, the Western world has fallen under the spell of the furoshiki, its big brother with a sustainable spirit. This versatile rectangle of fabric can easily replace wrapping paper for the time it takes to offer an elegantly presented gift... before being used again as wrapping paper on another occasion.

In addition, Japanese fabrics also continue to be used in traditional arts such as ikebana (flower arrangement) and calligraphy, where they serve as backgrounds or decorative supports.

Throughout centuries of history, Japanese textiles have demonstrated unique craftsmanship, where refined techniques, noble materials, and cultural symbolism intertwine with remarkable consistency. Wagara have continued to evolve while maintaining a deep attachment to nature, beliefs, and seasonal cycles. Whether geometric, floral, animal-inspired, or landscape-inspired, these textile patterns reflect both an aesthetic and a worldview nourished by Shintoism and Buddhism. Today, this textile heritage continues to live on, as much in traditional kimonos as in contemporary fashion, interior design, and everyday accessories.